The above is all IMHO. Please do respond and dialogue! I will jump in and respond at times and continue to write more psychological and business-based blogs with the focus on practical and real-time solutions.

The above is all IMHO. Please do respond and dialogue! I will jump in and respond at times and continue to write more psychological and business-based blogs with the focus on practical and real-time solutions.

During risk assessment facilitation training sessions, people often ask me: “Do I have what it takes to be a good facilitator?” This is an important question, and it applies to managers or anyone who runs meetings and gives presentations. The response is actually simple; for just a moment, throw out all the models, the facilitation techniques, and the psychological tests. Knowing who you are, your strengths and weaknesses, and using them to your advantage is the key behind being an effective facilitator.

Learning to facilitate can be anxiety provoking, because it calls on so many internal and external faculties that must be used simultaneously. Facilitating can be equated to a juggling act; one must listen to ideas being offered, animate quiet people, contain dominant participants, and think about what question should be asked next—all at the same time!

When asked, I offer this comprehensive definition of what it means to be an effective facilitator: “A great facilitator weaves overriding strategies with specific facilitation tools, while monitoring the group process using interpersonal radar.” “Fortunately, you don’t have to do it perfectly to do it well!”

The idea in this last sentence usually provokes a reaction. Most people argue: “If I’m going to the trouble of standing in front of a group of people, I need to do it perfectly!” In fact, this sentiment often echoes inside the heads of new facilitators during the workshop process: “You idiot! Why did you ask them that question?” and “Oh no! No one is talking! What should I do?” That mean little voice can be quite effective at letting us know when we are performing at a less than “perfect” standard.

Perfection in facilitation isn’t necessarily the same thing as effective facilitation, however. As a result, one of the first major factors in becoming an effective facilitator may simply be to learn how to ignore that negative voice, the voice that demands some vague standard of perfection in facilitation. Effective facilitators develop techniques and strategies for making that inner voice work for them instead of against them.

No standardized test consistently determines who will or will not be an effective facilitator. The answer lies in how you interact with people; your willingness to keep practicing, make mistakes, continue practicing; and your ability to trust yourself, as well as the people you are facilitating. Taken together, proficiency in these areas will create effective facilitators. What psychological and other inventories can help you with is achieving greater understanding of your personal facilitation style—your own unique approach to working with others, effectively infusing all of who you are into the facilitation.

For example, there are tests that can determine if you are more introverted or extroverted. A person who is introverted by nature is one who becomes energized through his or her own ideas. The extroverted person, on the other hand, gains energy from interaction with other people.

Based on this simple distinction, it appears at first glance that the extroverted person would be the better facilitator. After all, one of the ““golden rules” of facilitation is to demonstrate good interpersonal skills. An extroverted person would tend to focus more on the group participants and listen more closely to what they have to say, instead of retreating inside themselves to their own thoughts. Although this theory may be true, it has never been proven; there is no data to suggest that introverts can’t also be exceptional facilitators.

Indeed, a person who is too extroverted may not be a good listener at all. They might make a good keynote speaker, but that requires a very different skills set (some of which are used in facilitation) in order to be successful.

One of the best facilitators I ever observed—

someone who originally thought she could never be a good facilitator—was a quiet, introverted young woman I will call “Carol.” When facilitating, Carol would position herself between the flipchart easel and the group, a “cardinal sin” of facilitation. She would ask the group a few intelligent, provocative questions to get them started and then simply record the discussion on the flipchart as the participants took off on her creative questions.

She would also sense when the discussion on a topic began to wane. Politely, in a quiet voice, Carol would jump in and ask the next question, once again eliciting a round of responses from the group. She would then turn around to the flipchart, writing with her back to the group, instead of maintaining eye contact with the participants. Once again, Carol broke another important facilitation rule: always maintain good eye contact. Interestingly, Carol’s tactic had the effect of forcing the group to talk to each other, which was needed at this particular point in the meeting. As she wrote with her back to them,

Carol would continuously nod her head as they made pertinent points, occasionally turning to the group to interject a question or clarification. She did this just often enough to let them know she was still present. It was the combination of both turning her back while still maintaining contact in these other, subtle ways that made her facilitation so effective.

At the end of a ten-minute session, she turned away from the flipchart and back to the group, showing them what she had captured from their discussion. The group was astounded at the amount of information she had collected in such a short period of time. In addition, she had been so unobtrusive that after a while they almost forgot she was present during their discussion.

When the group is so involved in carrying out the task that the facilitator exists almost solely to capture their ideas, it represents facilitation at the highest level. At these moments, the whole group experiences a synergy that feels energizing, highly creative, and purposeful. To the facilitator, it feels effortless.

What we are witnessing in scenarios like this one is the ability of a person to take a potential liability or “imperfection” for facilitating—Carol’s introverted nature—and turn it around for everyone’s benefit. In other words, Carol used her interpersonal radar to detect what would and wouldn’t work in the facilitation. Her innate talent for creative thinking framed ideas and questions that kept the conversation on track. She took advantage of her quiet, less social nature basically to stay out of the group’s way, maintain her neutrality, and act as a conduit between the group’s ideas and the flipchart.

There was yet a third obstacle that Carol used to her advantage. Carol is very short in stature, and research suggests that short people command less power and authority in managing a group’s dynamics than their taller counterparts. Once again Carol broke the “rules” using her height to her advantage. Because she was so short, she was able to pull the flipchart very close to the group to hear them better in the slightly noisy room. Later, when her proximity to the group was brought to their attention, group members either did not notice it; or if they did, they did not feel that it was obtrusive. In fact, they felt a closer bond to her, because it seemed to balance her otherwise more distant nature.

Instead of trying to present herself as something she was not, Carol decided to use all of herself in the facilitation to as much advantage as possible. She broke some rules, but because she trusted that her group had the knowledge to provide the needed information, she was able to latch onto the value of their ideas instead of her own. This was not easy for her to do; it took a concerted effort to focus outward. Because she focused on the group’s ideas, however, it became easier and easier as time went on. By the end of the facilitation course, she was beginning to develop an effective facilitation style that was uniquely hers.

A week later, Carol’s director called me to express his surprise. He had sent Carol to the course because he knew she was an excellent auditor, despite her reluctance toward presenting information to groups. The director noted that since her return, Carol had co-facilitated a portion of a company-wide audit conference to rave reviews. I last heard that she and other co-workers who attended the training were taking turns facilitating the department staff meetings to keep their skills fresh.

While it appears that this is an isolated example and a unique event, the fact is that it could hold true for any other facilitator. Carol was bitten by what I call the “facilitation bug,” and she definitely isn’t the first. Many technical professionals become quite dedicated and skilled at facilitation and begin applying its principles to many areas of their lives.

In my opinion, these people are effective because they are committed to developing and refining their facilitation skills. They practice, practice, and practice. Effective facilitators are also supportive co-facilitators, who do whatever they can to make their partners look good and make their partner’s job easier when they work together.

Effective facilitators are risk-takers, willing to stretch as they apply their facilitation skills and previous experience to a variety of group situations. For example, a number of organizations that have been running facilitation workshops are beginning to facilitate all types of meetings in their organizations, often at higher levels.

Many facilitators find that as they broaden their endeavors, they need to increase their understanding of organizational culture and dynamics to handle the more challenging situations they encounter. Facilitation requires practitioners to use all dimensions of their personalities. As the situations become more challenging, growth must occur to meet new opportunities.

Anyone—introvert or extrovert—may have what it takes to be an effective facilitator. It is more an issue of personal interest, dedication, and willingness to meet a substantial challenge. It doesn’t always require extensive technology, though knowledge of technological options is always useful. It doesn’t take an advanced degree. Effective facilitators believe in the value of facilitating and, most importantly, they have fun with it

Originally published in the association magazine of the Institute of Internal Auditors.

© 2019 JPA-International

During my career working on board-level corporate governance, I had the opportunity to observe companies, mostly large, consider and apply corporate governance rules and leading practices in their companies. Rules often come through the SEC, while leading practices are often driven by investors and proxy advisory firms.

Over the years, I saw scrutiny of the audit committee ramped up through the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and the Compensation Committee under pressure from the Dodd-Frank Act. But one of the mandatory committees (at least for public companies) that has so far avoided scrutiny is the Nominating and Governance Committee. While I don’t mean to pick on Nom & Gov, I’ll share my observations about this committee and its role in board functionality.

It’s important to recognize that the Nom & Gov is largely responsible for who is on the board. It is this committee that identifies and vets candidates for the board, makes recommendation about director policies including tenure and retirement, oversees board organization, oversees director orientation and performance assessment, oversees CEO succession planning, among other responsibilities. In spite of its responsibilities for the overall functionality of the board, I question whether the committee is “on board” with improvements in governance. I’d like to see this committee step up its game – get with the program if you will.

In recent years, I’ve heard talk about director term limits and mandatory retirement. I’ve also heard some horror stories about directors needing to be retired from a board for one reason or another, but no one on the board having the chops to make it happen. When I think about the responsibilities of a board, I cringe at the thought of dysfunction around that table – because there’s so much at stake.

Advising and counseling management, addressing strategic issues, and making tough decisions is not easy but it is rewarding. Hard decisions must be made, and directors need to be willing to make those hard decisions whether they impact senior management, or their colleagues around the board table. If the board can’t reach a consensus, they should have conflict resolution policies in place to help guide them to a conclusion.

Directors get their positions largely because they’ve distinguished themselves in some way: they’ve founded companies; led organizations, many through troubled times; developed a particular area of expertise where they’ve made some significant contribution. What I don’t understand is when I hear that a board was weak when the going got tough. How is it that they could not draw on their experience, recognize their obligation to act in the best interest of the company, make tough decision and see it through? Surely over their careers they’ve faced crossroads, had to make tough decisions, and sometimes deliver bad news. It’s not easy to do, but it comes with the territory. A board that can’t do this is weak, and Nom & Gov needs to take its share of responsibility for that.

Nom & Gov has responsibility to identify and select for consideration board candidates that have the backbone to get going when the going is tough. Selecting new director candidates requires investigation, robust interviews, and being sure that director candidates will work well with the existing board. When a candidate is elected to the board, Nom & Gov must orient the new director to the board and how it operates. It’s likely that the new director will be appointed to a committee, so Nom & Gov must ensure there is an appropriate orientation for the committee’s work as well.

Sometimes it will be necessary to rotate a director off the board – maybe even when the director did not expect to be rotated off (this action is usually taken with the blessing and participation of the board chair). This is part of the territory too, so the Nom & Gov Comm can’t be weak here either. And if you are the director on the receiving end of such action, accept your responsibility to put the board’s needs before your own, accept the situation graciously and move on.

Need Help?

The Board Governance Services team @ JPA can help. Reach out to us via our website or LinkedIn, or call John Morrow on 908/432-0576.

Want to Share Your Views?

If you want to share your views on this blog, please write to [email protected].

[1] Proxy access is when long-term shareholders meeting certain requirements are able to include their own candidates for director into the company’s proxy statement for voting by the shareholders. If a company does not allow proxy access, shareholders would have to publish their own proxy statement with the opposing directors at significant cost to the long-term directors.

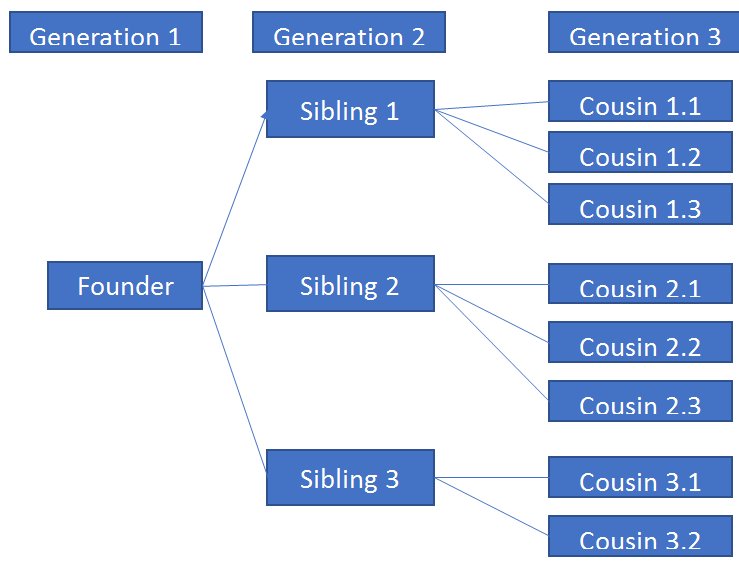

A global family-owned company is beginning its leadership transition from Generation 2 (children of the founder) to Generation 3 (grandchildren of the founder). This is a very difficult transition and many family-owned companies don’t make the transition successfully. The point here is, in a non-public company you have the ability to be creative in solutions.

The company is a huge global conglomerate largely identified in the consumer-products and pet-products space, employing thousands globally. It is owned and overseen by the family, and beginning to transition its leadership from Generation 2 to Generation 3. G2 was three siblings that were retirement minded, though struggling to establish an appropriate balance of power among their three families – the undertone being that no one family would have more power in the company than the others. G2 agreed to retire from the company in two-to-three years, which was a time frame they believed sufficient for transition. The board included the G2 siblings and 4-5 other directors that had played key roles in (or with) the company at various times in its history.

The company is a huge global conglomerate largely identified in the consumer-products and pet-products space, employing thousands globally. It is owned and overseen by the family, and beginning to transition its leadership from Generation 2 to Generation 3. G2 was three siblings that were retirement minded, though struggling to establish an appropriate balance of power among their three families – the undertone being that no one family would have more power in the company than the others. G2 agreed to retire from the company in two-to-three years, which was a time frame they believed sufficient for transition. The board included the G2 siblings and 4-5 other directors that had played key roles in (or with) the company at various times in its history.

Two of the three G2 families had three children, and the third family had two. Some of the G3 cousins were involved in the business and others were not. A few of those involved in the company had leadership roles and the others had staff roles. There was one G3 cousin that was very aggressive about the company, and this is whom the others were hoping to keep from becoming too powerful.

Recognizing the complexity of the challenge G2 reached out for help and impartiality.

As a family business the board had few, if any, governance rules they had to follow. The board had the freedom to be as creative in their governance as they wanted to be, but G2 struggled to think beyond traditional board roles.

The transition from G2 to G3 in the family business is a particularly turbulent transition, because the founder (G1) is likely not around and the G3 members likely don’t have the same shared values that G2 often has – having been raised together in one household.

We spent some time with family members in both G2 and G3, as well as the non-family members of the board, to understand whether they remained committed to the company being family-owned and governed. We were assured of the importance of the family legacy in the business as well as the various sensitivities so we could propose a workable solution.

We proposed that the cousins in G3 rotate the chair of the board position every 3-5 years (exact number of years to be agreed among the G2 and G3 family members). Consider there are three families with two or three cousins in each family. To simplify this discussion, let’s call them 1.1-1.3, 2.1-2.3, and 3.1-3.2 (see chart).

The proposed plan respects the wishes of G3 to continue their leadership in the company. It provides for each G3 cousin to get a deep background on the company, lead strategic projects and present to the board before becoming chair of the board. As each G3 chair of the board completes their term and becomes “emeritus” they are able to coach their cousin through the difficulties of being the board chair. Each of the three families have representation on the board and in significant strategic roles at any point in time.

There will be challenges with this or any other scenario for balancing power over the company among three families. The difficulties will have to be worked out within the family and with consultation and guidance from outside board members. If this proposal doesn’t work, the families and the board can consider alternatives. Hopefully, this proposal breaks the board out of thinking about traditional board succession and encourages them to be creative in problem solving.

The transition from G2 to G3 is the first real test for a family company because the ownership/leadership transition can get emotional and complicated. That said, the success of this transition could set the company up for successful transitions in following generations. As the generations get larger this particular model likely won’t work, but the creativity used here applied to future transitions could mean the difference between success and failure.

G2 had other options to consider: (1) maintaining ownership and hiring a professional board, or (2) selling the company. G3 showed interest in ownership and leadership, and we wish the company continued success.

Summary:

Asking incisive questions and taking action on its findings. All members should be involved in setting the agenda. Meetings should be carefully planned so that priority business is acted upon in a timely manner. Decision-making processes need to be determined before a crisis occurs. Each committee needs to evaluate its unique needs when laying out its ground rules. Meetings should start and end with summaries so that all members have a common understanding of what has transpired and what the priorities are.

In the five years that have passed since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act gave audit committees greater responsibility for overseeing public companies’ accounting, financial reporting, internal controls, and audits, many of these corporate governance watchdogs have become quite adept at performing their expanded duties. Others, though, have not developed this expertise as rapidly as others. This article offers eight time-tested best practices for improving numerous aspects of audit committee performance, as well as insights from three seasoned CPAs who have led or served on the audit committees of many organizations.

1. Create and adhere to a written charter that identifies audit committee functions, authority and responsibilities, and the skills and experience its members must possess for the committee to discharge its duties and function effectively.

Without a strong written charter to guide it, an audit committee is unlikely to know where it’s going, much less how to get there. The charter should specify what skills and experience audit committee members need to help the group achieve its goals. At least one member should be a “financial expert,” as defined by SOX and the SEC . The charter also should specify frequency of meetings, topics to be covered, and the nature and frequency of the committee’s communication with the organization’s senior managers, as well as its internal and external auditors. One of the charter’s most important functions is its record of the various powers and authorities the committee must possess, independent of the organization’s senior management. The audit committee should be free to obtain the information it needs to assess adherence to rules, regulations, and the organization’s core values. An audit committee that has adequate authority to ask appropriate questions and get informative answers is in a better position to provide useful commentary and recommend necessary action.

This ensures the organization and management are responsive to stakeholders, whether they are shareholders in an SEC-registered corporation or bond-holders with a stake in the fiscal management of a municipal government agency. The SEC requires audit committees of listed companies to prepare an annual audit committee report. When applicable, this requirement should be written into the charter. Although an annual report may not be required for some organizations, it is good practice for a committee to resolve to prepare one. Other audit committee functions and powers laid out in its charter should include:

The charter also should give the audit committee the right to monitor officers’ expense accounts and use of corporate assets and consider the results of audits in these areas and to ensure the adequacy of the scope of and plan for internal and external audits, internal controls over mandatory financial reporting as well as earnings statements contained in press releases. In addition, the charter should codify the audit committee’s authority to periodically review the organization’s code of conduct for adequacy and recommend changes as necessary and its right and responsibility to review any complaints the organization receives about its accounting, internal controls, or financial reporting and monitor their resolution. This includes confidential, anonymous reports by employees and others regarding questionable accounting, auditing, or other matters.

Finally, it is essential for the committee to conduct an annual review of the charter’s adequacy in light of new business conditions, laws or regulations and recommend changes to the board of directors as necessary. The charter should clearly state the audit committee’s responsibility to periodically review its own effectiveness. The charter should require the committee to plan its agenda a year in advance, leaving room for unanticipated items to be added, and that certain standing topics be included every year. For example, the one standing agenda item could be to review and approve the chief audit executive’s annual plan.

Leadership Principles for Audit Committees

Run the audit committee in a professional manner. Members of the audit committee are role models. Shareholders, the board of directors, and senior management are watching you. The audit committee chairman establishes the “emotional tone” of the group. The audit committee chairman is especially responsible for preventing “groupthink” and “collusion.” Ask the hard questions to connect the dots. Make sure you know how (that is, by what procedures) different areas of the organization reached the end results and summaries before you. Regularly assess your performance.

2. Specify critical success factors as competencies audit committee members must possess for the committee to discharge its duties and function effectively.

First learn the business and its risks. Then become familiar with the accounting treatments unique to the business and prepare for all meetings. “It can be very challenging to read a 10-K three or four times, but it’s necessary,” says Paula Cholmondeley, CPA, who has been an audit committee chairwoman for three public companies—Ultralife Batteries, Albany International, and Denstply International—and one investment company, Gartmore Mutual Funds.

Cholmondeley strongly recommends that audit committee members spend time building relationships and diligently maintain their skepticism about issues and topics within their purview. One of her greatest concerns is that audit committee members stay abreast of the latest developments relating to accounting rules, legislation, industry, and the company. “We need two levels of knowledge,” she says. The general level is addressed by a lot of courses business schools offer audit committee members on how the committee should function.

“But it’s more difficult to keep up with specific accounting knowledge,” she says. “The key accounting policy reviews by my committees enable the companies and their management to educate us on a few issues a year.” She and her fellow committee members also study literature from auditors and attend presentations on new accounting pronouncements.

3. Identify committee core values that reflect those of the organization and establish written procedures that foster open communication, equitable dispute resolution, and active participation by all committee members.

Audit committees need to encourage mutual respect and cooperative interaction with auditors and the organization’s staff and senior management. According to Dennis H. Chookaszian, CPA, who serves on three audit committees and is chairman of the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council, “the chair should provide the appropriate ‘tone at the top’ to help instill a control orientation within the organization.” He says the chairman also should identify priorities for the entity’s audit team and oversee the evaluation of the personnel, quality, frequency, and scope of the entity’s financial and internal audit functions.

The chairman also must prepare the committee for significant challenges, whether relatively new, like understanding enterprise risk management and its corporate governance implications, or longstanding and growing, such as the struggle to build and retain a high-quality staff of financial professionals. Similar challenges and responses are in play in the government sector, says Colleen Waring, CPA, who was deputy city auditor in Austin, Texas, prior to her retirement at the end of 2006. In Austin, the city auditor is appointed by and reports to the city’s audit and finance committee, which the mayor chairs.

The city charter and the ordinance governing the city auditor’s role and responsibilities guide the committee’s actions. Waring says the city auditor meets regularly with individual committee members to hear their questions, comments and concerns.

4. Reserve the right to invite any group or individual to an audit committee meeting.

As the audit committee chairman of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Chookaszian has helped the committee establish good working relationships with the exchange’s CEO, CFO, chief audit executive, external auditors, and other members of the board of directors. “These connections are essential to the audit committee’s success,” he says.

The chairman must establish regular communications with these senior managers to obtain their views on what the audit committee should focus on and keep them apprised of audit committee activities. In his view, the closest relationship the chairman should have is with the head of internal audit. “And,” he emphasizes, “that position should be a direct report to the audit committee.”

Additionally, the head of internal audit should have an administrative reporting relationship to someone not involved in financial reporting, such as the general counsel. While Austin’s audit committee offers a “safe haven” to individuals it interviews in executive session, Waring says it still asks incisive questions, objectively evaluates answers, and takes whatever action is necessary to resolve issues within its purview.

5. Ensure all members actively participate in setting the committee agenda, and whenever possible, avoid conducting committee business between meetings.

When it comes to audit committee effectiveness, advance planning, members’ technical skills, and relations with senior management are of paramount importance. Audit committees should request that the organization’s chief audit executive and senior financial officer attend each meeting and address the committee as a whole.

Interactions between the committee and management should not be limited to written correspondence or interaction with only the audit committee chairman between meetings.

“It’s essential that the audit committee create a schedule of meetings for the coming year, including an agenda for each meeting,” Chookaszian says. The agenda should identify the highest priority items for each meeting, such as reviewing the company’s SEC form 10-K. He also strongly recommends holding quarterly meetings with the external auditor, the CEO, the CFO, and the head of internal audit. Further, he says, a good way to evaluate the audit committee’s performance is to conduct an annual confidential survey that elicits committee members’ views on the committee’s effectiveness.

As chairman, Chookaszian accepts responsibility for providing information to the committee and, as necessary, getting the CFO and internal audit chief’s help to do so. “The chair has to ensure that committee members have all the information they need on new issues and company activities,” he says. One way he delivers such information is by preparing for the audit committee and senior management an annual status report on the company’s financial and internal audit functions.

When meeting with the audit committees she chairs, Cholmondeley uses a checklist that tracks all the regulatory tasks that must be completed during the current year. “We also have an annual calendar with all the topics for each meeting in the year,” she says. The calendar has a section for fixed agenda items (for example, ethics, internal audit, SOX issues, executive sessions, and financial reports). It also has a section for meeting specific fixed items—usually items from the checklist, such as a review of the yearend auditor’s report. And there are sections on key accounting policy reviews and functional presentations.

Cholmondeley plans her audit committees’ agendas at the beginning of the year by identifying the topics to be covered. Just before each meeting she also requests topics from audit committee members and management, and then she adds to the original agenda new topics that require discussion.

AICPA Audit Committee Effectiveness Center Recognizing the need for increased support for audit committees, the AICPA created the Audit Committee Effectiveness Center, an online center available through the AICPA Web site at www.aicpa.org/audcommctr. The center was created in the public interest and includes the following key features:

The AICPA Audit Committee Toolkit was created to help guide audit committees. The Toolkit, which is available in versions for corporate, not-for-profit, and government entities, includes a variety of programs, checklists, matrices, and questionnaires designed to help the audit committees understand and execute their responsibilities. New tools are continually developed and released when available.

Over 40,000 copies of the print versions of the Toolkit are in circulation. Each tool in the Toolkit is available in the online center in various formats including Word, so users can download and customize it for use in their own organization for free—the AICPA asks only that users include a notation acknowledging the AICPA’s copyright on the tools. Print versions of the Toolkit can be purchased. This allows the AICPA to recover its production costs.

The Audit Committee Matching System is another key feature of the center. This is a free searchable database of AICPA members who are willing to serve on audit committees and boards of directors. While each party (candidate and searching organization) must perform its own due diligence on each other, the matching system is an ideal way to bring the CPA skill set to audit committees. More than 2,000 AICPA members are registered in the database, and searches are conducted regularly.

A third feature of the center is the E-Alert System created for visitors to the site to register for an e-mail notification of updates to the site, release of new tools, and other matters of interest to audit committee members. The E-Alerts are also a free service and available to AICPA members and non-members alike.

6. Formulate decision-making processes and procedures for resolving stalemates.

Committee members have to agree to some ground rules, which should relate back to the charter. All audit committees are unique, and so is each organization’s culture, says Cholmondeley. Procedures should reflect the specific needs of the individual committee and organization.

Objective criteria should be developed in advance for evaluating prospective external auditors or internal audit executives. This helps the committee overcome personal preferences and pressure from management when evaluating a particular audit firm, consultant, or job candidate.

Objective criteria should be developed in advance for evaluating prospective external auditors or internal audit executives. This helps the committee overcome personal preferences and pressure from management when evaluating a particular audit firm, consultant, or job candidate.

Another inhibitor to timely decision making can be a lack of knowledge on particular issues facing the organization. Committees should obtain additional information from the organization whenever necessary to facilitate informed deliberation. “You have to learn the business,” Cholmondeley says. “That takes time and a willingness to read product literature, visit company facilities, and meet employees. But it’ll make you a more effective member of the audit committee.”

7. At the beginning of each meeting, review the previous meeting’s highlights.

Guiding principles and focus easily can be lost in the details of a complicated business. In addition to highlighting results from previous meetings, start by reviewing the company’s written organizational vision, core values, and critical success factors.

Continue referring to them as you review documents. Working with her colleagues on each audit committee she chairs, Cholmondeley measures the committees’ effectiveness in several ways. On a fundamental level, she reviews the checklist to see whether all the tasks were completed. “But more important,” she says, “is our collective sense of whether we’ve improved the organization over the past year. Is the finance team better able to deal with complex issues than it was a year ago? Have we improved our relationship with management? Do they consider our suggestions and act promptly on our requests?”

8. At the end of each meeting, summarize it.

After a meeting is over, each member should have a common understanding of key aspects of the meeting without referring to notes or minutes. For this purpose, summarize key decisions, actions to be taken, who will perform them and when, and the expected results.

Require each meeting attendee to specify what aspects of the meeting he or she felt were successful or helpful and what requires improvement. Discuss whether the organization’s vision and objectives are being fulfilled. Also committee members should encourage each other to organize and share in writing any thoughts they have following the meeting that would be helpful to the committee.

by John F. Morrow and Joan Pastor

John F. Morrow, CPA, is the AICPA vice president–business, industry and government. His e-mail address is [email protected]. Joan Pastor holds a Ph.D. in industrialorganizational psychology and clinical psychology and has consulted extensively for the AICPA on organizational and leadership issues. Her e-mail address is [email protected]. The authors wish to thank Robert Tie of the AICPA’s Communications team and Kayla Briggs of the Business, Industry and Government team for their assistance in preparing this articlen

Joan Pastor, Ph.D is a clinical psychotherapist and organizational psychologist with both teen and adult clients around the world. For more information on Joan or on the services her company offers, please call (760) 945-9767, email to [email protected], or write JPA International, Inc: 5054 Avenida de la Plata, Oceanside, CA 92057. Vist JPA International at www.jpa-international.com.