Succession planning – walking a tightrope

For over a year I’ve been working with a not-for-profit organization on its board-level governance and related issues. As with many organizations, its board has been weak, and needs to be strengthened. An additional challenge with this NFP is that it operates more like a family business than a typical NFP. This brings succession planning into mind – something with which we have great concern.

The organization was founded in the late 1940s by an individual for the benefit of a particular ethnic community. The founder managed the operation until his death in the late 1970s, when his protégé and the protégé’s wife took over the operation. At this point, the husband (CEO) is nearing 90 years-old and the wife (administrator) is in her later 70s. They are reticent to turn anything over to someone else because they can’t tolerate losing control; strategy is not their forte and they have missed the boat on a number of opportunities; they have also been weak in protecting the revenue stream. They’ve enjoyed good health, and have an incredible work ethic and dedication to the organization. Their only child, a son in his 50s, has no interest in the organization in the full-time sense, but he is very dedicated to it and would likely be willing to take responsibility for an aspect of overall management. However, many in the organization are not comfortable with his competencies, and his wife, who exerts a lot of influence over him, is toxic to the organization.

The wife/administrator has a huge role in the organization, wearing (too) many hats. I expect no one in their right mind would be willing to take over her role as it currently exists, but there are a few folks in the organization that might take on 2 or 3 of her various roles – some are actually chomping at the bit to do so. Coaxing her to see these people as successors, and having her give them responsibility, accountability, and coaching has been difficult.

The struggle is getting the wife/administrator to accept the need to plan for succession. Trust is a big issue; for one thing, I must be careful not to push too hard or she will lose trust, AND she needs to trust the people that might take over her various roles. As with many NFPs, there isn’t a lot of money to pay people so the idea of attracting people from outside likely won’t work. The people that will take on these roles do so out of love for the organization.

This is where succession planning is as much about psychology as it is about good business. In this case, whomever is leading the effort has to tiptoe around the incumbents, while also ensuring that the successors are developing appropriately. It’s further complicated when the incumbents are not open to change because only they know best. And we need to be mindful that the incumbents will still be around after they retire and could undermine (even unknowingly) the new leaders.

Summary

I continue to tread carefully here, taking opportunities to make points about succession whenever I can. Following are some key messages from JPA Board Governance that are important for the board and management to act on:

- It is absolutely vital to have a succession plan to ensure continuity of an organization.

- The board should hold management accountable to have regular succession conversations. Maybe it’s as simple as an annual touchpoint with management. Maybe a semi-annual discussion. Frequency will depend on the organization, but it should be done on some regular basis. If succession planning is embedded in the organization’s way of doing business, the “threatening” part of the discussion goes away and everyone becomes more comfortable with the topic.

- Cross-training supports succession planning. Cross-training keeps colleagues educated, interested, and able to cover for each other when needed. The same could be said for collaborative management – developing a team by sharing challenges and seeking their input into solutions.

- It’s important to make succession a process, not an event. When someone takes on a new role, give them time to get comfortable with the role, and then coach them to think about their succession. Make succession something people address regularly. At JPA Board Governance, we teach that succession planning begins when you develop the job description, right through recruitment, hiring, performance management, development, goals, etc., to ensure on-going job fit.

- If controlled/owned by a family, the family element needs to be addressed. Family leaders should have regular, open conversations with family members about succession. To avoid doing so will cause business as well as family problems.

- Think beyond the immediate successor. At the NFP I expect the husband’s successor will be in his 50s or 60s, so I am thinking they also need to recruit someone in his 30s to be the successor after that. In the meantime, the 30-something can be learning all facets of the NFP, and develop strong relationships in the community served. This will help the 30-something be a strong and trusted leader when the time comes.

- Patience. Many people can talk about succession planning but few actually do it. Whether it’s facing their own mortality, or believing no one else can do what they do (or as well as they do it), or maybe they feel threatened by a rising star – succession is hard for an incumbent to address. Relatively speaking, being the consultant is easy (except for the being patient part).

Succession planning has long been a hot button of mine, and I am continually perplexed at how companies ignore it. This is especially true of public companies, and I fault the boards for not holding management accountable for the need to plan succession. By not having such a plan CEOs are derelict in their duties because that’s not in the long-term best interest of the company. And while I can accept the need for confidentiality, I cannot accept boards (some of them at very large companies) that don’t have a succession plan for the CEO – they too are derelict in their duties.

Help Needed?

The Board Governance Services team @ JPA is ready to help you manage through all board assessment challenges. You can reach us through our website, through LinkedIn, or by calling John Morrow on 908/432-0576.

Want to Share Your Views?

If you want to share your views on this blog please write to [email protected].

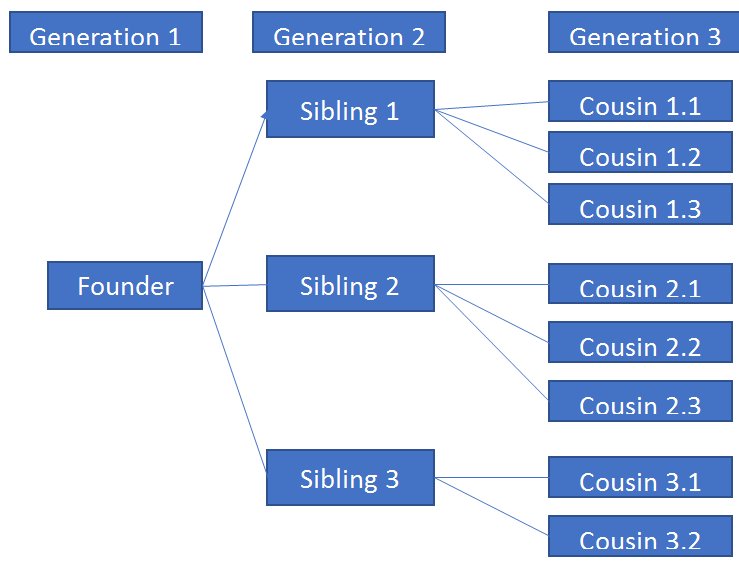

The company is a huge global conglomerate largely identified in the consumer-products and pet-products space, employing thousands globally. It is owned and overseen by the family, and beginning to transition its leadership from Generation 2 to Generation 3. G2 was three siblings that were retirement minded, though struggling to establish an appropriate balance of power among their three families – the undertone being that no one family would have more power in the company than the others. G2 agreed to retire from the company in two-to-three years, which was a time frame they believed sufficient for transition. The board included the G2 siblings and 4-5 other directors that had played key roles in (or with) the company at various times in its history.

The company is a huge global conglomerate largely identified in the consumer-products and pet-products space, employing thousands globally. It is owned and overseen by the family, and beginning to transition its leadership from Generation 2 to Generation 3. G2 was three siblings that were retirement minded, though struggling to establish an appropriate balance of power among their three families – the undertone being that no one family would have more power in the company than the others. G2 agreed to retire from the company in two-to-three years, which was a time frame they believed sufficient for transition. The board included the G2 siblings and 4-5 other directors that had played key roles in (or with) the company at various times in its history.