Does Your COACH Pass The Test

Assessments are a powerful tool in the business coach’s arsenal. Done correctly, they provide objective data and feedback that coaches can use to help clients identify opportunities for positive change. They can reveal both the big picture and personal idiosyncrasies that clients may need to either tone down or use to greater advantage. In the right hands, assessments can transform an individual or an entire corporation for the better.

However, done incorrectly—as they too often are—assessments can actually do more harm than good. That’s why prior to selecting a coach, you need to know some facts about the assessment process.

Start Here

First, let’s talk about what a test battery is. It means that your coach will conduct multiple assessments (more on this shortly). In selecting the most effective battery, a good coach will ensure that:

• Each assessment makes a clear contribution.

• Each assessment relates to the reasons why you desire coaching.

• Each assessment coordinates with the others, providing an in-depth understanding of your needs, strengths, and perceived weaknesses.

It’s very important to understand that not all assessments are alike. In fact, some have very little validation. One of the most popular assessments that organizations use today was vetoed for use in research and dissertations for this reason at the graduate school where I received my degree in industrial organizational psychology.

In addition, when it comes to conducting assessments, not all coaches are alike. I strongly believe that anyone using assessments needs to receive very thorough training—years of it, not just weeks or months. Coaches who lack this training will misuse even the best tests. In addition, they will be at the mercy of venders who promote worthless or even harmful assessments. Again, it isn’t enough for coaches to choose the most popular assessments, because some of the weakest and least statistically valid assessments are the most popular today.

Smart Assessments

Finally, even if an assessment is robust—meaning that its results are truly valid—coaches need to use it effectively. This includes:

• Clearly explaining the purpose and process of each assessment to clients beforehand.

• Describing the results of each assessment in language that clients can understand.

• Showing clients how to translate the findings into concrete, positive steps.

• Describing the strengths and limitations of each assessment so clients can give the results the proper weight.

Choosing A Coach

With these points in mind, how do you select a coach whose assessments will do good rather than harm? Here are two questions to ask up front:

1. Ask if the coach plans to use a customized test battery or merely administer one or two tests.

If a coach claims that a couple of assessments and an hour of information-gathering will be sufficient to develop an action plan, look for another coach. It takes at least four to five assessments for a coach to develop a well-rounded picture of a client.

In addition to asking how many tests the coach will administer, ask the purpose of each one. Also, ask how each assessment relates directly to your needs or your corporation’s needs.

2. Ask the coach what will happen after the assessments.

Too often, coaches provide the results of an assessment but offer little or no interpretation of these results. (One reason is that assessment reports can be very sophisticated, and many coaches themselves don’t fully understand them.) This is dangerous, because it means that the assessments won’t translate into insight and increased self-awareness. Instead, they have the potential to do serious damage.

In one case involving a Fortune 100 company, a coach gave a female senior executive a very powerful assessment. This woman, while definitely needing improvement in some areas, had worked extremely hard to pull herself up by her bootstraps and to succeed in a challenging job. However, her coach at the time interpreted the assessment results in a very superficial and negative way that left her feeling discouraged. The report itself was very murky, and a negative tone came through in it as well.

When I arrived later to gather information and conduct my own assessments, the woman was very nervous, and it took a great deal of effort on my part to persuade her to agree to go through the assessment process again. She was so pleased this time that she brought me the original assessment that caused her so much pain. I went through it carefully with her, tying it in with the feedback from my own battery of assessments. When she understood the whole picture—both her strengths and the beliefs and behaviors that might be getting in her way—she took ownership of the information. She’s now positive and confident, is clear on what she wants to achieve in her career, and is effectively grooming herself for those next steps.

In another case, a corporation brought in a psychologist and “expert” to assist a department troubled by infighting. The person’s solution was simply to give an assessment to everyone and then tell each participant, in front of the rest of the team, what they were doing right and wrong. There was no discussion on how to change their behavior to resolve differences positively; instead, the coach just got up and left.

The group was shell-shocked, and some members were devastated. Somehow, their top boss was referred to me, and after much debate about inviting a psychologist into their presence, they decided they were willing to try. Following my testing and feedback, the group went from hostile to eager to totally onboard, and the infighting ended. To this day, their now C-Suite-level boss and others from the same original team turn to me when they need to communicate delicate feedback or information, require team coaching, or are preparing for a restructuring.

What to Look For

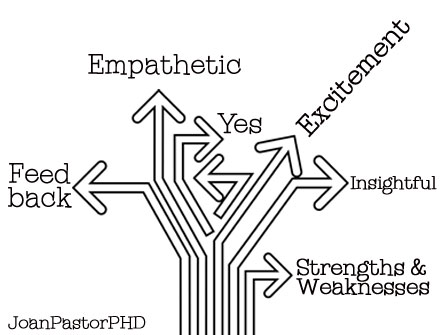

Good coaches give feedback that is not just accurate and constructive, but also empathetic and insightful—especially when it involves perceived weaknesses. People are excited about learning more about themselves, but many are also nervous about exposing what they deem to be their weaknesses. When coaches give feedback properly, it allows clients to step outside themselves and view themselves as a whole entity. Good coaches discuss weaknesses as openly as strengths, because those very “weaknesses” often have contributed as much to a person’s success as what we call their strengths.

For instance, I have another client who is in a powerful position in a Fortune 500 company, making decisions that impact many other people at the global company. One assessment I gave this client was an emotional intelligence assessment called the MSCEIT. This test reveals how well clients perceive, use, understand, and manage their own emotions as well as the emotions of others. The assessment revealed that he was very weak in accessing and integrating emotion accurately. However, another sophisticated assessment I gave him allowed me to determine that he was highly ethical.

Earlier in his life, this man saw the damage that emotion can cause, and decided to stay focused on reasoning and analysis. This emotional detachment gave him the ability to steadfastly do what he and the corporation agreed was best for the organization as a whole, despite the emotional reactions of others. Combined with his high level of ethics, it allowed him to become very successful. However, it also led to problems. For instance, because he kept his emotions at arm’s length, other people frequently perceived him as doing the same thing to them. In addition, many perceived him as manipulative.

In our work now, we focus on how he can best show his ethical self and learn to experience and show compassion, while allowing others to see that he has no other agenda than doing what is best for the company. He is also learning how to be transparent in appropriate ways, which is encouraging others to do the same in return. It’s been fun and personally heartwarming to watch him unfold within himself and at the same time begin to read people and respond to them more accurately. He still meets with resistance, as his job is to institute major change, but people—including his boss—now better understand where he is coming from, and are joining forces to support him. In the process, they’re learning how to better embrace the disruptions that are necessary for everyone to grow.

Summary

Clearly, assessments can be a powerful tool for good—but only when the right person conducts them.

So don’t automatically assume that any coach and any assessment will do the job. Instead, seek out a coach who has years of training in using assessments, will custom-tailor a battery of well-validated assessments to your specific needs, and will translate the results into practical information you can understand and positive steps you can take. Your coaches won’t be shy about testing you… so don’t be hesitant about testing them!